New Jersey Shields Its Fragile Shoreline Ecosystems

Among the piping plovers and marsh grasses of New Jersey’s scenic coast, environmentalists and communities are busy creating green infrastructure to shield the shorelines from storm damage while supporting local economies. The Coastal Resilience Collaborative, the New Jersey Resilient Coastlines Initiative, and the NJ Climate Adaptation Alliance are bringing financial and tactical resources to bear on restoring reefs, wetlands, marshes and dunes.

According to data published by Lloyd’s in 2016 and cited in the report “Financing Natural Infrastructure for Coastal Flood Damage Reduction,” “Coastal wetlands in the northeastern United States are estimated to have reduced property damages from Hurricane Sandy by 10 percent, totaling more than $625 million in avoided damages. These wetlands also reduced damages from annual flooding. For example, marshes in Ocean County, New Jersey have reduced average annual losses by 20 percent.”

This report was published by Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), University of California Santa Cruz, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Lloyds Tercentenary Research Foundation.

However, this is a small fraction of the total cost. According to the New Jersey Coastal Resilience (NJCR) website, Hurricane Sandy caused over $50 billion in damage, with $37 billion in New Jersey.

The NJCR website says the state’s bays, ocean, beaches, dunes and marshes play an important economic and ecological role. To preserve them, TNC develops green infrastructure that includes plants, wetlands, dunes and reefs. This assists its community partners with eroding shores, increasing floods, and rising seas.

Beaches in New Jersey attract birds in large numbers. Coastal ecosystems in the state are also home to oysters, clams, crabs, scallops and flounder, the NJCR website says.

“We have been working a lot with communities since Hurricane Sandy to help them integrate nature-based solutions to respond to the challenges of climate change – whether that’s sea-level rise, coastal erosion, or other types of flooding,” said Patty Doerr, director of marine and coastal programs at TNC’s New Jersey office. “And through our work, we’ve identified some key barriers to communities moving forward with doing projects.”

Two of these barriers are funding and capacity. The networks that are working to protect the coast from storm damage are leveraging their resources to resolve these issues.

Regional Assets

What unique challenges does the Northeast face when it seeks to strengthen its coastal resilience? The Middlebury report shows how the Northeast finances coastal green infrastructure.

“Coastal marshes in the heavily developed northeastern United States are conserved primarily through public ownership,” the Middlebury report says. “Offset restoration is funded by both public and private sources. Beach restoration… is common in some states and is primarily paid for by local assessments on property or by sales taxes. Post-disaster funds have supported habitat restoration for risk reduction – specifically, targeted funds for coastal restoration after Hurricane Sandy.”

The authors evaluated the financing options that are being used for coastal restoration now in the Northeast. Although the Northeast has strong governance and funding compared to some other parts of the nation, institutions are not set up optimally to reduce flood risk and create natural infrastructure.

What solutions could help the Northeast expand its financing for green coastal infrastructure? The Middlebury report recommends combining funds for risk reduction with funds for flood recovery. This could include using green bonds and catastrophe bonds that are structured to support risk-reducing investments before or after disasters.

To use green bonds successfully, these projects require revenue sources to repay the bond buyers. They also require bond-performance standards showing they have reduced flood risks.

Green bonds are well-suited to investors who are looking for long-term, low-risk, steady-performance investments, the Middlebury report says.

Special purpose districts, like the ones that fund stormwater infrastructure, could also play a role. The National Flood Insurance Program could assist with the process.

Local natural geography and ecosystems, community governance and socioeconomic status, national financial conditions, and green infrastructure policies all influence the appropriate choices of financing tools.

New Jersey could do much more to explore these options. Doerr said many groups in the state have received federal grants since Hurricane Sandy. The Nature Conservancy has put together two rounds of funding that were supported by donors and foundations. One of these, which it awarded to two communities in 2017, was $25,000. The second, which it is awarding to three to five communities in 2018, is $75,000.

Proactive Collaboration

According to the Middlebury report, one of the largest barriers for financing coastal resilience involves the need to pinpoint locations where natural infrastructure can provide the most benefit. The data tools TNC has developed solve this problem for New Jersey.

“Coastal restoration has been an issue in New Jersey since even before Hurricane Sandy, but since then, there has been a lot of work in the coastal-reconstruction world by conservation organizations, planning organizations, and government agencies,” Doerr said.

Recently, the state and its partners have formed the Coastal Resilience Collaborative. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Fish and Wildlife Federation have invested extensive resources in it.

“We’re collaborating to make sure we’re taking a holistic look at the coastline and what the land looks like,” Doerr said.

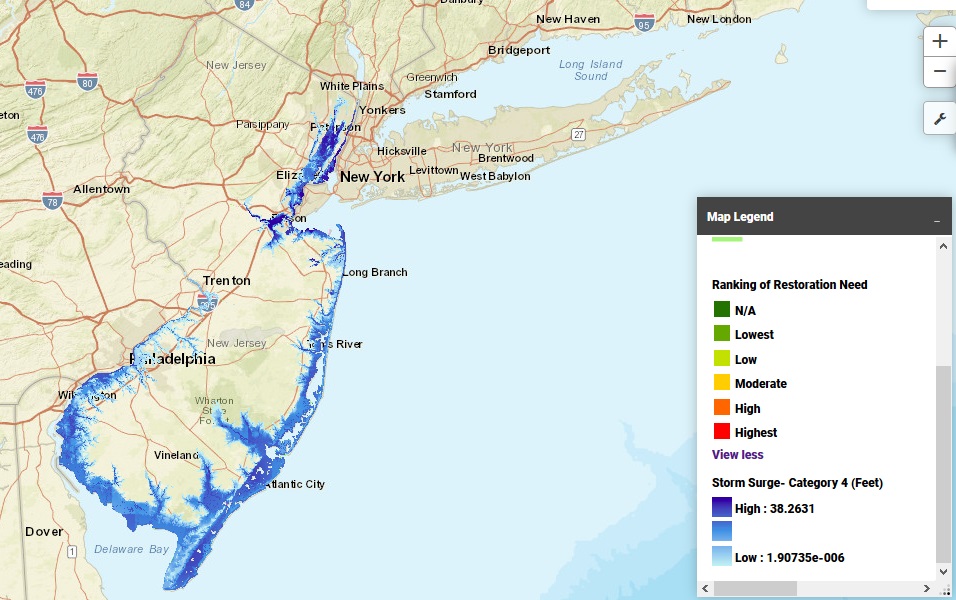

In this situation, ‘taking a holistic look’ involves using advanced data tools that produce dramatic images of the hazards New Jersey faces. For example, the image below shows what a Category 4 coastal storm does to the state’s coastal communities. With sea level rise, the situation will be even more severe.

The collaborators can use the Coastal Resilience website, which is where all of the maps shown in this article were created. TNC developed this site together with a group of partners to map out the risks that specific communities face and make plans to address them. The site was funded by NOAA as part of the TNC-led NJ Resilient Coastlines Initiative. TNC produces coastal-resilience-planning data for other states also.

Project partners include American Littoral Society, Barnegat Bay Partnership, NOAA Office for Coastal Management, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, Rutgers University, Stevens Institute of Technology, and United States Geological Survey.

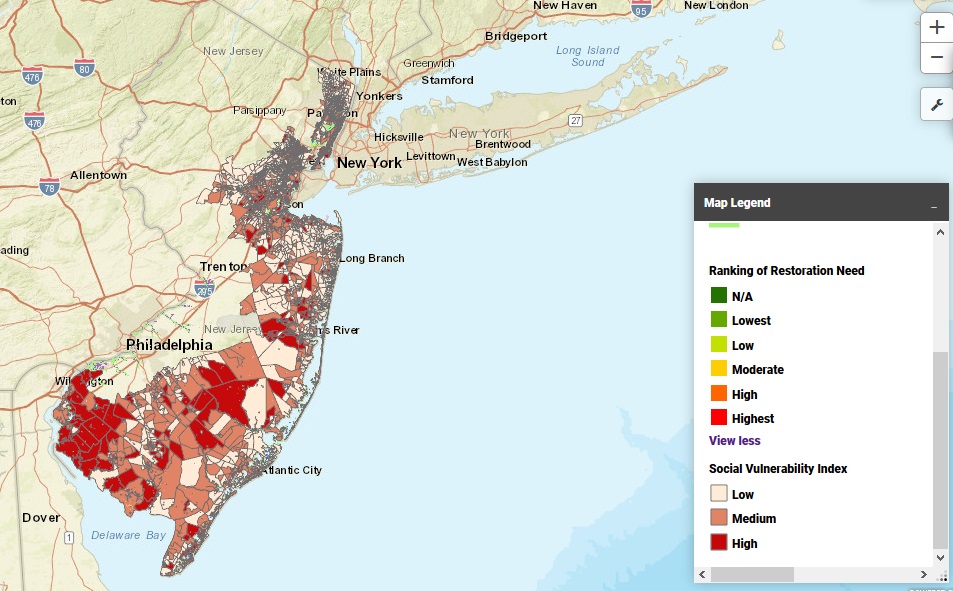

The mapping tool also shows socioeconomic risks. In the graphic below, the darker blocks are areas that are less socioeconomically stable. This shows where targeted assistance might be most beneficial.

In the Northeastern United States, higher-income communities tend to cluster along the coast.

Hurricane Sandy’s legacy has energized coastal resilience efforts, Doerr said. The storm motivated communities to think about long-term planning after their recovery.

“It’s human nature to think about what you’re seeing on a daily basis,” Doerr said. “But a lot of them are thinking big-picture and long-term now. And they’re thinking about how to deal with the sea level rise and the less-intense storms.”

Living Shorelines

One of the solutions TNC recommends is the construction of living shorelines. According to the report “A Framework for Developing Monitoring Plans for Coastal Wetland Restoration and Living Shoreline Projects in New Jersey,” a living shoreline is a built or engineered structure that may be composed of a variety of natural or other materials. These shorelines include native flora and fauna. They reduce erosion while improving habitat.

Living shoreline projects can make use of technological solutions like fiber logs, oyster castles, and shell bags, according to a handout from TNC.

Oyster reefs deliver many benefits to nearby communities in New Jersey. TNC’s website says it is collaborating with United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, and Rutgers University Haskin Shellfish Research Lab to construct 3,000 feet of oyster reef in the Gandy’s Beach Preserve along the Delaware Bay.

The construction materials include oyster shells and oyster castles. These castles are interlocking, stackable concrete blocks. The shells were recycled by a restaurant in Atlantic City.

The oyster reef will become self-sustaining as the oysters settle there to grow and mature. The oysters also improve local water quality.

Coastal Wetlands

According to the monitoring report, wetland projects tend to be larger than living-shoreline projects. They may raise marshes, improve habitat, or assist hydrology.

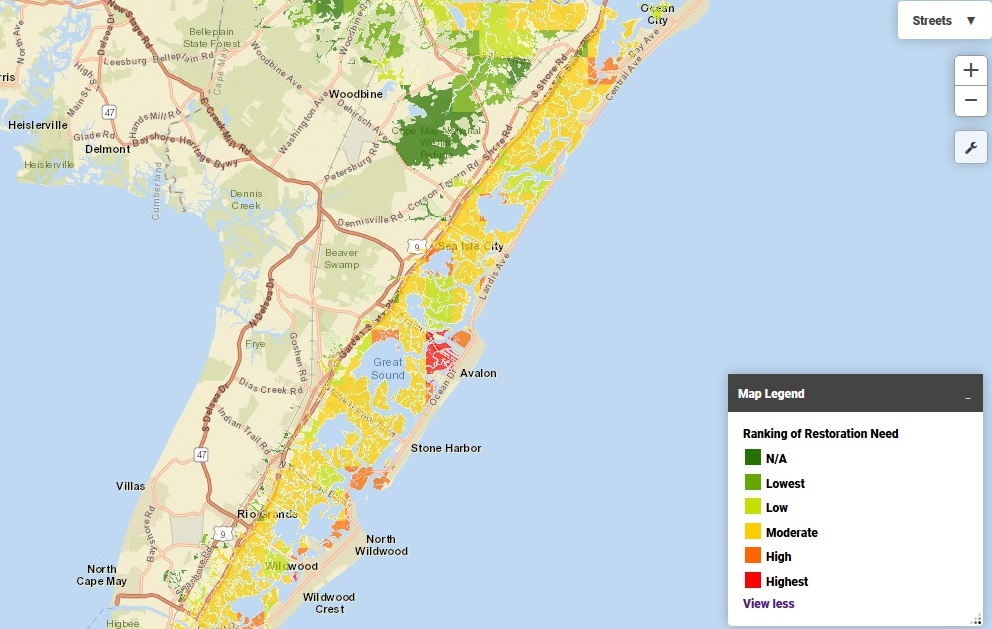

In 2007, TNC completed a restoration project for South Cape May Meadows. The coastal restoration website reports that TNC restored beach, dune and wetland ecosystems and installed a water-management system. The map below shows the high-risk wetlands are color-coded in red.

This project vastly benefits coastal property owners. An economic study showed that the value of the flooding protection will be at least $2 million. The project will prevent $17.3 million in residential flood damages over the next 50 years.

The ecosystem benefits are also highly valuable. According to the study, restoring migratory bird habitat at this location has also brought in an estimated $313 million every year to the area due to bird-watching tourism. The beach recreation improvements are valued at $11-12.5 million per year.

As these partners expand their shoreline projects, the state may be able to maintain its tourism and avert flooding. But global warming’s increasing flood risks mean that these organizations are racing against time.

Note: The Nature Conservancy has donated to Conservation Finance Network.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.