Conservation Finance 101

The work of protecting critical habitats and natural resources requires a clear vision, skilled practitioners and financial resources. While vision and capacity are essential, little can be accomplished without funding, which has become a subject of growing interest in the conservation community.

What exactly is conservation finance, and how does it work? Why is it increasingly relevant to land and resource conservation today? Which sectors does it involve? These are the questions the

The practice of raising and managing capital to support land, water, and natural resource conservation.

Network works with our partners to address.At the

The practice of raising and managing capital to support land, water, and natural resource conservation.

Network, we seek to accelerate the pace and scale of land and resource conservation, restoration, and stewardship by expanding the use of innovative and effective funding and financing strategies. While public sector funding for conservation is critical, it is not sufficient. We must also catalyze private sector capital, which is far more plentiful than public or philanthropic funds, to conserve nature at scale.This page offers an introduction to the field of conservation finance. It seeks to orient newcomers to the field, introduce some basic concepts and a few more advanced ones, and offer directions for where to go to learn more. As you dive in, it may be helpful to refer to CFN’s Glossary of Terms.

Note: funding typically refers to “free” money, like grants, whereas finance either requires repayment (debt) or the securing of an equity interest.

What is ?

Conservation finance is a broad term that encompasses the many tools and strategies for securing the funds needed to implement and sustain a given conservation objective. Conservation finance includes both traditional fundraising involving grants from government, foundation, corporate or individual sources as well as strategies that go beyond traditional grants to tap market-based approaches, including private investment in mitigation funding, debt for nature swaps and payment for ecosystem services, among others. The crux of conservation finance is that someone must pay for an environmental good or service (or, for avoided costs).1

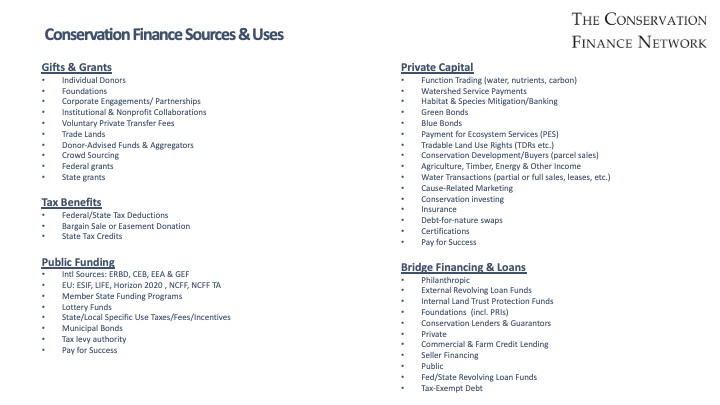

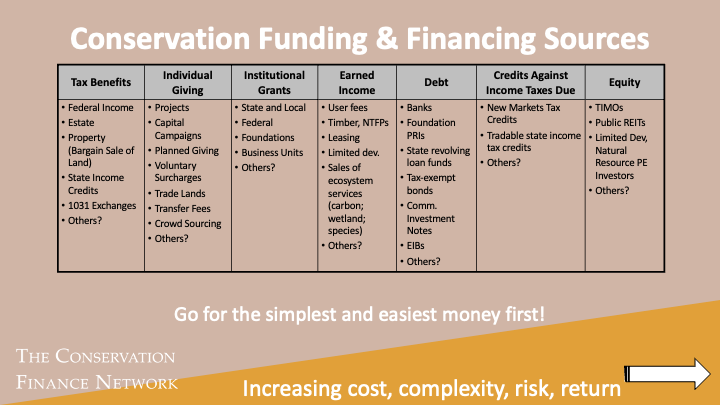

This introduction describes conservation finance tools which range from simpler to more complex types of funding and finance to support conservation. In many cases, charitable and government grants are the most suitable and straightforward for conservation projects. Increasingly, new sources of conservation finance are emerging from efforts to monetize “nature’s goods and services” in new ecosystem markets involving carbon, water and biodiversity. As private investment grows, conservation practitioners are utilizing financial tools from other parts of government, banking, and asset investment to unlock new project possibilities. This growing medley of options for securing project funds is what we call conservation finance. The image below illustrates the variety of conservation funding and financing sources:

Conservation finance can be broken into four categories of sources that sometimes overlap:

These sources are further explained below.

-

For-profit investment, which depends on cashflows from, or associated with, the conservation project

A key conservation finance principle is to go for the easiest and simplest sources of money, first. It can be easiest to secure a donation of land (Bargain Sales, “Tax Benefits”), more complicated to secure large foundation grants (“Institutional Grants”) and orders of magnitude more challenging to secure revenue from the sale of carbon credits (“Earned Income”) or to partner with a private investor (“Equity”).

Government Grants

Government grants have traditionally funded the vast majority of conservation projects. Government grant programs provide support for a range of activities that include the acquisition of land or conservation easements, restoration, planning and capacity building across multiple landscapes that include forests, farmland, wetlands and coastal habitats. A perennial conservation finance strategy has been the use of ballot measures, typically known as referenda or initiatives, that have generated significant amounts of conservation funding at the state and local levels.

Charitable Grants/Donations

Philanthropic support can be provided by individuals, foundations, and corporations. This is a lesser but still significant source of funding for conservation. Traditionally, philanthropic funding has been provided in the form of grants, either targeted to specific projects or less often for “general operating support.” Increasingly, foundations are putting both their endowments and grant funds to work by providing other kinds of support such as program-related investments, low-interest loans, guarantees, interest rate sweeteners, and more. Internationally, some philanthropies, in collaboration with governments, have helped to capitalize conservation trust funds in 50 countries to manage long term financing for protected areas, biodiversity conservation or other purposes.

Cashflows or Earned Income

When there is a source of income, or cashflow, attached to a conservation outcome, this can unlock a new source of conservation finance. Cashflows can come from a wide range of sources including municipal, state or federal tax revenue for government-funded conservation projects; entrance or use fees for parks and other valuable resources; sustainable timber harvest; and payments for ecosystem services like carbon credits.

For-Profit Investments

Cash flows also create an opportunity to attract private investment, a complex but growing source of funding for conservation. Because investors require a return, this can create challenges for nonprofit organizations accustomed to utilizing grants, or “free money.” But there are numerous ways in which private capital can advance conservation outcomes, ranging from parallel investing in sustainable forestry and regenerative agriculture to blending market rate capital with public and philanthropic funding to increase the scale of conservation. Private investment in conservation has grown significantly over the past 10 years with the proliferation of “impact investment” firms that are deploying capital in sectors that range from forestry and agriculture to wetlands and fisheries, typically balancing “financial return” with “impact.”

Specific Tools

Here are some examples of specific conservation finance tools. For more examples explaining conservation finance tools and how they work, view CFN’s toolkits.

Loans

Once a source of income has been attached to a conservation project, it enables access to “debt financing” in the form of government and private sector loans or bonds. It is important for this enabling income to be consistent over time because it allows investors to trust that if they loan an organization more money than it has today for a given project, the investor can be paid back in the future. Loans can take various forms with the most frequent being short-term bridge loans, which are typically repaid by government grants or fundraising. To learn more about bridge loans, also known as “interim finance,” see CFN’s toolkit on bridge financing.

Pay for Success

Payment for success financing is being utilized in Ohio’s Wayne National Forest. Upfront costs for a trail system are repaid by taxes on increased tourism activity around the conservation area. The Iowa Soil and Water Outcomes Fund also employs a pay-for-success model when it pays farmers to implement practices that improve water quality and carbon sequestration and then sells the water outcomes to government to meet their effluence limits and the carbon outcomes to corporations to meet their sustainability targets (see Duke case study). In a third application of this model, the Forest Resilience Bond, the upfront costs of forest thinning to reduce catastrophic fire on a national forest and sedimentation downstream are reimbursed by a public agencies and a water utility that might otherwise face much higher expenses in treating water quality (see Duke case study).

Ecosystem Service Markets

Conservation-oriented approaches to more traditional real asset investments (e.g. timber, agriculture, and ranchland) are an increasing area of focus. Carbon markets can be a source of revenue for land trusts and landowners (see CFN toolkit).

Water Funds and Clean Water State Revolving Funds

Water is another ecosystem service that has been monetized in various initiatives across the country. Examples include the support by New York City to protect its watershed to minimize the probability of having to spend much more to treat polluted water downstream, or the Portland Water Authority’s funding of upstream forest protection to keep the water clean. (see CFN toolkit).

Though largely focused on “grey infrastructure” and difficult to access for many communities, Clean Water State Revolving Funds have been a source of revenue for certain conservation projects (for example, the State of Pennsylvania’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund supported a Lyme Timber forestland investment).

Blended finance

Increasingly, conservation projects are combining various sources of public funding and private investment to increase the scale of protection and restoration initiatives. One celebrated example is the Forest Resilience Bond, which mobilizes private capital to complement existing public funding to finance ecological restoration of forestlands in the Interior West (see Duke case study).

Regardless of where you and your team are positioned in the conservation space, conservation finance is a powerful, interdisciplinary toolset to have at your disposal. It combines the frameworks of banking, investing, community development, philanthropy, and government to maximize conservation outcomes.

Who does conservation finance?

Many organizations have expertise in specific elements of conservation finance. For example, national organizations such as The Nature Conservancy and Trust for Public Land each have

The practice of raising and managing capital to support land, water, and natural resource conservation.

programs that are expert in accessing state and federal funds for conservation. Organizations like Quantified Ventures can help put together pay-for-success deals and other outcomes-based financing tools while global organizations such as the World Resource Institute and World Wildlife Fund have developed financing tools and initiatives. Organizations like The Nature Conservancy have created impact investment branches. Agricultural companies like Danone are increasingly focused on sourcing from farms using sustainable practices. Government agencies like the U. S. Forest Service and Department of Defense are creating new conservation finance strategies. Private investment firms like Lyme Timber, Sustainable Land Management Partners and Dirt Capital Partners, among others, use private capital to achieve sustainable land management and long-term conservation outcomes. Land trusts across the country are creatively adapting and using local, state, federal, and private resources to sustain their work.Internationally, various groups focus on conservation finance. The Conservation Finance Alliance has developed a helpful guide and established various working groups focused on specific financing issues, while the International Land Conservation Network has made conservation finance a key focus. Forest Trends has established an Ecosystem Marketplace to track key trends in these markets. Other organizations within specific countries, as well as collaborating globally, are monitoring and helping to advance conservation finance initiatives.

In short: the suite of conservation finance players is long and growing. We look forward to learning from and sharing success stories across our network!

The Network seeks to support our community of practice in the following ways:

-

Convene: We bring together conservation finance practitioners through our annual Roundtables and other events.

-

Coach: We provide education about conservation finance principles through our annual Boot Camp, and in targeted geographies as funding allows.

-

Connect: Through our website and e-news, we share cutting edge information about the field of conservation finance.

-

Catalyze: We introduce and workshop emerging conservation finance initiatives with the potential to achieve scale and increased impact.

We encourage you to explore CFN’s offerings online and through our in-person events and workshops as you progress on your conservation finance journey.

Explore our website to learn more:

-

Conservation Finance 101: A video describing the basics of conservation finance

-

Articles describing innovations in the field of conservation finance

Other Resources:

View the videos below for an introduction to conservation finance and some example case studies.

Thanks to Truett Sparkman for his contributions to this piece.

Part 1 - Sources and Uses

Part 1 covers an overview of conservation finance, key trends in the field, and gets into specific sources of project financing or matching funds.

Aired live on February 5th, 2020 2:00pm ET to 3:30pm ET

Part 2 - Case Studies

Part 2 uses case studies to highlight effective strategies for utilizing different types of funding and how to blend them.

Aired live on February 7th, 2020 2:00pm ET to 3:30pm ET

Footnotes

1: That entity could be a public agency, taxpayer, consumer, a regulated/compliance buyer, utility, or others. The challenge is that many environmental services are classic “public goods” - things like clean air and water - that we all enjoy and can’t prevent others from enjoying