Financing Urban Water Protection and Management

The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) January 2017 report “Beyond the Source: the Environmental, Economic and Community Benefits of Source Water Protection” highlights water funds as a strategy for urban source water protection. 40 percent of source watersheds around the world show high-to-moderate levels of degradation. This can put water and food security at risk and negatively impact economic growth.

The report defines water funds as institutionalized mechanisms that connect upstream and downstream water users through integrated financing, governance and management. These mechanisms can take a variety of forms, but share the following characteristics: “a funding vehicle, a multi-stakeholder governance mechanism, science-based planning, and implementation capacity.”

Andrea Erickson, managing director of water security at TNC, said water funds are the best way TNC has come up with “to cross jurisdictional boundaries… and connect work in cities to [protection] solutions upstream.”

Erickson said she hopes TNC’s report will convince readers that urban source water protection is a valuable investment with an array of co-benefits and get them thinking about whether a water fund might be right for their city. “Ultimately, we are trying to mainstream the idea of investment in natural infrastructure. And water funds are a way to do that.”

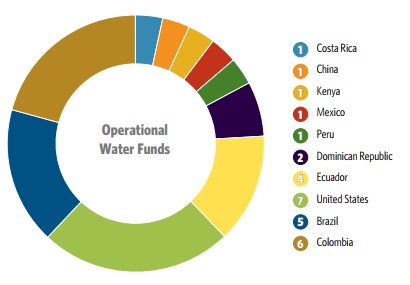

TNC has worked on 29 water funds globally, 22 of which are in Latin America. An additional 40 projects are in the design phase. A number of TNC’s current projects are included in the report.

The Need for Source Water Protection

The current degradation of source watersheds is primarily the result of the development and deforestation – as well as the use of fertilizers containing high levels of nitrogen and phosphorous.

The report says cities have traditionally dealt with water security issues through the development of “gray infrastructure” – manmade storage and treatment facilities. It shows the natural infrastructure provided by forests, wetlands, and other ecosystems is often a more cost-effective option than its man-made alternative.

The report’s authors found that four out of five cities can meaningfully reduce water pollution through land protection and improved agricultural practices.

In addition to improved water quality and quantity, TNC’s report illustrates an array of stacking benefits associated with source water protection. These include increased carbon storage and climate mitigation, better soil retention, protection of wildlife habitat, reduced fire frequency, and lowered risks to fisheries.

Erickson said implementing water funds also helps to “make people more aware of the value of nature.”

Source: TNC, Beyond the Source report (p. 10)

Financing Source Water Protection

The report says there is massive potential for cities around the world to improve water quality and quantity through the protection of source watersheds. However, implementing this work requires huge financial investments in land protection. TNC estimated that an annual increase of $42 billion to $48 billion is necessary to reduce sediment and nutrients by 10 percent in 90 percent of watersheds globally.

According to the report, no single source of funding can be relied upon to finance source water protection around the globe. Instead, raising and sustaining consistent funding at such a large scale will require a diversity of funding flows.

The report points to three ways in which water funds can be scaled through increased investment. These include strengthening public funding flows, bringing in new sectors of investment, and demonstrating the value of natural infrastructure as an alternative or complement to gray infrastructure.

Erickson said the key to establishing diverse funding flows is revealing multiple values that attract a variety of payers. “The reality is that there’s more likelihood [of raising funds] when more than one payer sees value. [It’s important] to hone the business case for different sectors.”

There must also be mechanisms in place that allow a variety of players to financially contribute, Erickson said. For instance, “corporations don’t want their money mixed with public money, so you have to figure out a way to capture multiple flows.”

In addition, Erickson said, “different payers come in at different times.” For instance, local food and beverage companies tend to be early adopters. Establishing sources of public funding like tariffs or taxes tend to be longer-term endeavors.

According to the report, most global investment in source water protection comes from public sources, specifically from the “3 Ts” – taxes, tariffs and transfers. Public sources tend to be large-scale and long-term, adding critical predictability to this work.

”“Public funding is always going to be big,” Erickson said. To ensure the surety of public flows over time, calls for investment need to be made “on a strong business case that isn’t about one administration or leader.”

While public funding will remain critical, Erickson said “we want to make sure not to leave private flows behind, for instance corporate money and philanthropy.” Philanthropic funding can be especially important for start-up flows. These funds can demonstrate proof of concept, building the confidence of potential future investors.

Erickson said it’s not an ‘either or’ situation. “The longer-term win is to ensure that private investment grows on top of [consistent] public funds.”

Bridging Funding Gaps

While stable sources of long-term funding are critical, water funds often require significant upfront infusions of capital. In some cases raising the initial funds to move forward requires borrowing funds to bridge a gap. Tight timelines and large-scale funding requirements make this scenario more likely.

According to the report, projects’ start-up funding needs may open access to large-scale investment opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t have existed. However, getting a project to an “investment ready” point can be difficult.

In general, projects must be in the $15 million to $30 million range to be considered “investment ready” for traditional capital markets. Project developers must also be able to guarantee a fast pace of implementation, which means garnering the participation of upstream communities early in the process. Ventures that have already secured long-term cash flows, through taxation for instance, are also more likely to attract private investment.

The report lists a number of loan repayment options. These include taxation and private bonds, transfers and private bridge capital, and tariffs and private securitized payments. The Edwards Aquifer Protection Program in San Antonio provides an example of bond repayment through taxation. Other examples are provided in the report.

While the report lays out what TNC has learned about bridge funding through experience, Erickson said that this piece of the financing puzzle still hasn’t been figured out. “There’s a call in the report for those in the finance sector to help [TNC] work this part out.”

Erickson said, “Source water protection is not always something against which cities can take out loans.” This could be true because a city doesn’t have the credit history to take on loans or because it isn’t legally allowed to recognize water as an asset against which funds can be borrowed.

The question of “how to get financing institutions comfortable with financing source water protection” is central to TNC’s current work, Erickson said. “We need smart people to help neutralize risks” – and to develop long-term revenue flows that can be used to guarantee financing.

In addition to de-risking water investments, Erickson said there will have to be a culture change around this work. “People in the water sector are generally very conservative. There needs to be a culture change in how they think about and manage risk.”

Looking Beyond the Money

While figuring out how to fund source water protection is critical, Erickson said “More money doesn’t mean we have solved all problems.” It is also critical to invest in “build[ing] social and political capital.” This includes identifying leaders in the private and public sectors to champion this work, from the early start-up phase to implementation.

Erickson said “the magic sauce of engagement” is always important. For civil society groups like TNC, this includes work with communities, organizations, and leaders across sectors. Erickson said it’s important to “look for common ground and platforms from which we can work together to succeed.”

According to Erickson TNC is actively working to capture and disseminate knowledge about water funds across geographies and sectors. This work has been undertaken through reports like “Beyond the Source,” trainings, and relationship-building with stakeholders such as cities, utility providers, and financiers.

TNC has also created an online Water Funds Toolbox that breaks down the pre-feasibility, design, creation, operation and maturity phases of water fund development. According to the report, work being done to spread knowledge about water funds is accelerating the pace of implementation and increasing the effectiveness of funds.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or email the author via our contact form.