Investing in Rainforests in the Global South

(Credit: Jules)

Funneling money toward forest conservation in the developing world may sound easier than it is. Once one gets into the weeds of implementing sustainable-forestry-finance frameworks like REDD+ at an international level, the challenges of climate finance come to the surface. This year, the game plan is changing to expand this financing space. United States nonprofits and investors will have new opportunities to help rainforest conservation flourish.

“I would say REDD+ is now poised to deliver significant emissions reductions in the next 5-10 years and to meet substantial demand from markets that are emerging around the world,” said Duncan Marsh, director of international climate policy at The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

TNC is one example of a United States-based NGO that has been active in protecting and restoring forests in developing nations for many years. Most recently, the nonprofit has become involved with the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Climate Promises

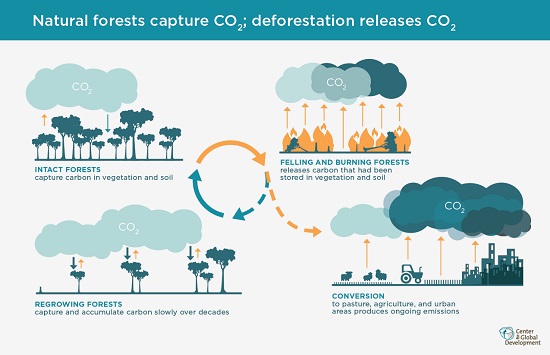

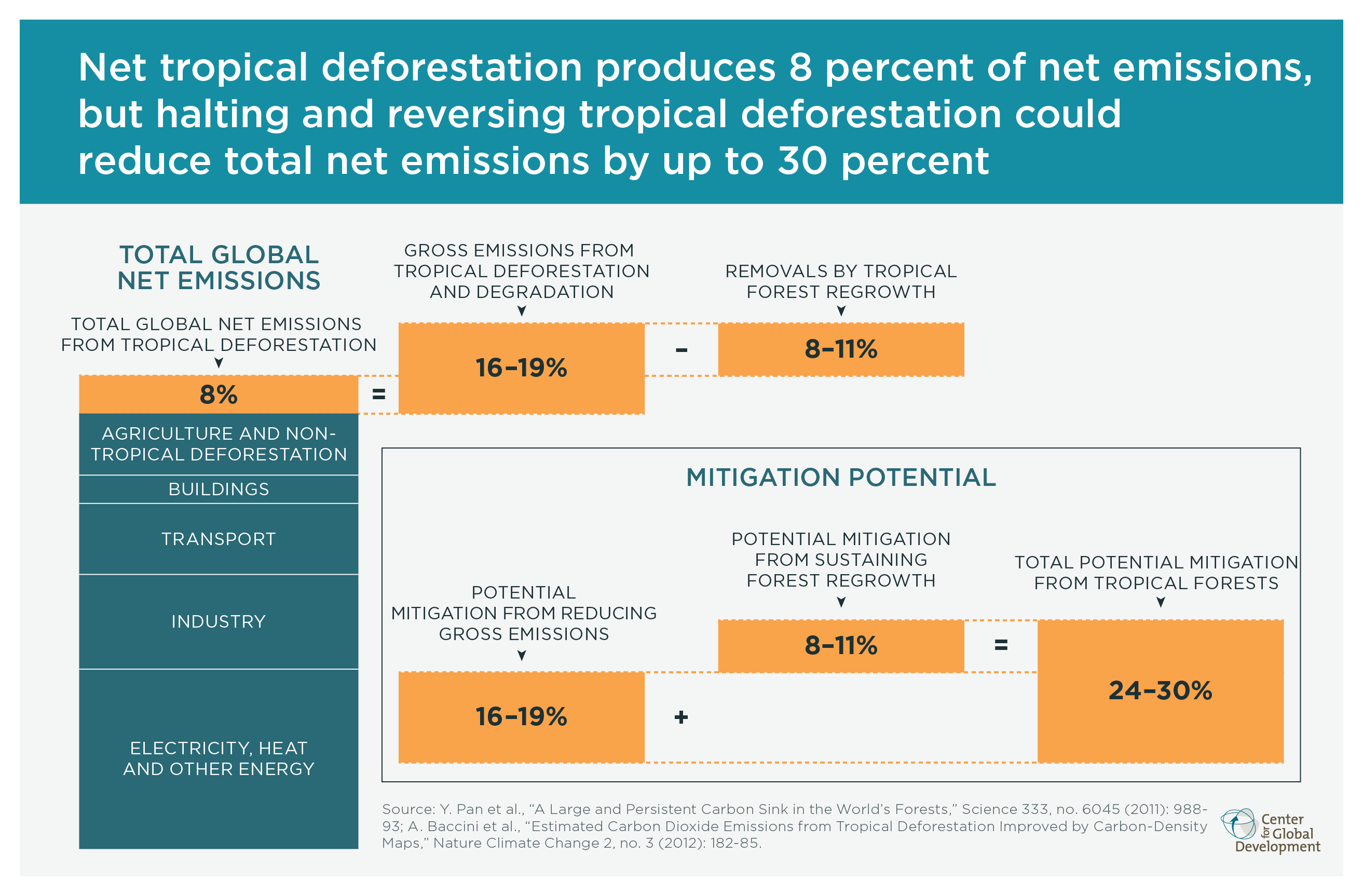

Saving forests in the global South is an attractive horizon for climate policymakers to aspire to reach. This is because 24-30 percent of the total potential for mitigating climate change can be provided by halting and reversing tropical deforestation, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“Stopping all tropical deforestation, plus continuing to allowing tropical forests to regrow and mature forests to capture carbon, would cancel out 31–37 percent of current annual emissions,” said Jonah Busch, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD), and Jens Engelmann, former research assistant at CGD, in an online white paper.

However, there are some caveats, Busch and Englemann said. “Sustaining the current pace of forest regrowth would require continually identifying new lands available for reforestation. Greater areas of reforested land would be required to capture the same amount of carbon. Forest regrowth is already taking place.”

New Momentum

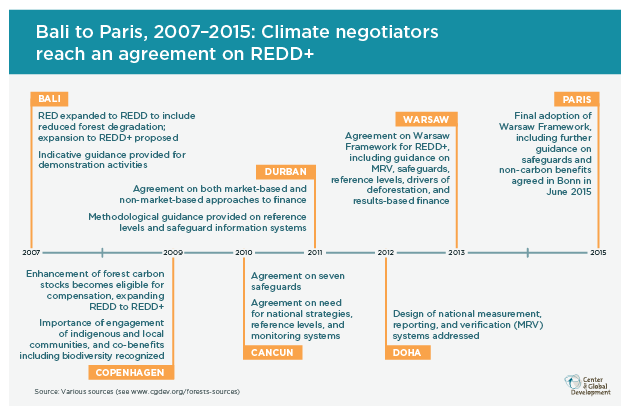

The United Nations developed REDD+ to improve forests’ ability to store carbon. It does this by reducing carbon emissions from deforestation, limiting forest degradation, and supporting sustainability and conservation.

According to Marsh, developing nations came forward in the mid-2000s and said they’d like to resolve the massive absence of incentives for forest protection in the existing clean development plan by “taking on commitments to reduce emissions from deforestation as well as through sequestration – and being awarded for this through an international framework.”

That is why REDD+ was created because the Coalition for Rainforest Nations proposed it.

“That was a real turning point around the attention to this issue,” Marsh said.

Over 70 developing nations have signed up to participate in the program. But so far, its ability to secure financing has been limited. Last year, Overseas Development Institute and Heinrich Boll Stiftung published a report on climate finance, “10 Things to Know about Climate Finance in 2016,” with a graph showing that REDD+’s resources had plummeted during the past several years.

Meanwhile, the United Nations has been working hard behind the scenes to give this potentially powerful climate-finance program more impact. During the past few years, it has struggled with developing a solid, workable structure to route financing toward the high-value cause of forest conservation in developing nations.

This requires paying attention to existing structures in each country. “REDD+ has to fit on top of the existing governance frameworks in countries. Land use has a number of layers of governance and management,” Marsh said. “[These are] institutions that need to be taken into account when one designs programs for forest conservation and other activities.”

Program developers have created the REDD+ Early Movers Programme and are setting up bilateral agreements to facilitate funding. Marsh said Norway, Germany and the UK are creating these arrangements with other nations.

“There were expectations that we’d be able to see significant emissions reductions from forests by this point, but those were assuming there would be local carbon markets in place that would be major drivers of those emissions reductions,” Marsh said. “Obviously, that hasn’t happened. But that’s been due more to the slow emergence of broader climate change policy than to any failings of REDD+ itself.”

Meanwhile, developing nations have been improving their capacity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has been creating and refining standards.

There has been an unexpected amount of public investment entering the space, Marsh said. Norway has taken the lead, followed by Germany, Spain, the UK, Australia and Japan.

Results-Based Payments

In an attempt to tap into results-based payments from the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which has been collecting resources for climate finance in developing nations with mixed success, decision makers who lead the REDD+ program have successfully negotiated with the GCF board.

This led to a decision at the board’s 17th meeting on July 5-7 in Songdo, South Korea about a plan for retroactive, results-based forestry conservation finance. The specifics of the implementation, which is being viewed as a pilot, are still being hammered out behind closed doors. Video footage shows the public decision.

“This is really a pilot that’s looking to mobilize finance for REDD+ to incentivize actions and to generate lessons that we can apply to the future,” said GCF Board Member Caroline LeClerc during the Songdo meeting. “This is quite a complex undertaking doing a RFP for results-based payments for REDD+. It raises a number of issues. There’s a sequencing of intertwined strategic and technical issues at play here. We are probably not in a place where we can agree that all the parts of the RFP are here today.”

During the meeting, members of the board evaluated the results-based payment proposal. Their viewpoints varied.

“I will confess that I was a skeptic,” said GCF Board Member Larry McDonald. “And as I have learned more about this topic, I have appreciated more the importance of it and its great potential for climate mitigation. I consider the secretariat paper a very good initial outline of this. We would not be in a position to agree to an envelope size until we see the finished RFP and scorecard and fully understand the process. We’re off to a good start. We look forward to continued good work in this area.”

Earlier this year, GCF initiated its first REDD+ transaction by approving a substantial financing package of $7.9 million USD for Ecuador. This will support its national goal of halting deforestation by 2020. According to the GCF website, this funding will be used to improve agricultural and livestock production practices to reduce deforestation. It will also support loans that fund the expansion of sustainable farming and deforestation-free products.

GCF’s resources are substantial, but funds from the private sector will be needed to make a massive impact on climate change. According to a second article by Busch, GCF has received over $10 billion USD in pledges, but the $2 million that the United States pledged may not be delivered.

Earlier funds have attempted to route resources toward REDD+ with mixed success, Busch said. GCF can learn from these experiences. The slow-moving $736-million Carbon Fund, a consortium of 11 donors, is hosted by the World Bank. This fund has started or is about to start results-based payment negotiations with Chile, Mexico, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Costa Rica. It also is considering 15 more programs, Busch said.

Busch said that the Carbon Fund’s attempt to develop rules that worked for both public funds and carbon markets hampered its progress. It also was attempting to follow other requirements set by the World Bank, which further complicated the situation.

In contrast, GCF is not attempting to develop rules for tradable credits yet and is focusing on public funding. This greatly simplifies the process. Busch said that GCF is attempting to also reuse rules developed by the UNFCCC.

The process of predicting how many tons of carbon dioxide a given project will keep out of the atmosphere is challenging. GCF has assigned a value of $5 per ton to the projects at present.

The initial RFP is projected to be for $500 million.

“That’s a good start, but it’s nowhere near enough to capture the full potential of REDD+,” Marsh said.

“We understand that public investment will never be adequate to meet the full needs and opportunity for REDD+ to help mitigate climate change,” Marsh said. “From our perspective, it’s very obvious that we need to find ways to access private capital as well as public investment.”

“It’s a pilot that’s designed very much for governments,” said GCF Board Member Merete Pedersen. “At a later stage, how do we deal with engagement of the private sector in terms of picking it up and mobilizing it further than it is today?”

Bringing the private sector into the process will be crucial at a later stage. It would dramatically increase the funding available.

Note: The Nature Conservancy has donated to Conservation Finance Network.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or email the author via our contact form.