New Horizons for Market-Based Stormwater Management

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that communities must invest $150 billion nationally in the next 20 years in infrastructure to effectively manage stormwater. A 2017 report from the Willamette Partnership outlines economic instruments that can drive investment or create action to meet federal and state environmental goals. Incentives, subsidies, trading and mitigation hold particular promise.

“Working with the Market: Economic Instruments to Support Investment in Green Stormwater Infrastructure” builds on a meeting of the National Network on Water Quality Trading. The report was written by Carrie Sanneman, clean water program manager at Willamette Partnership, and Seth Brown, principal of Storm & Stream Solutions. It was developed in partnership with Water Environment Federation’s Stormwater Institute.

While there are major barriers to scaling economic instruments, Sanneman said, this report also offers opportunities to overcome these challenges in the context of stormwater management.

Defining Economic Incentives for Stormwater Management

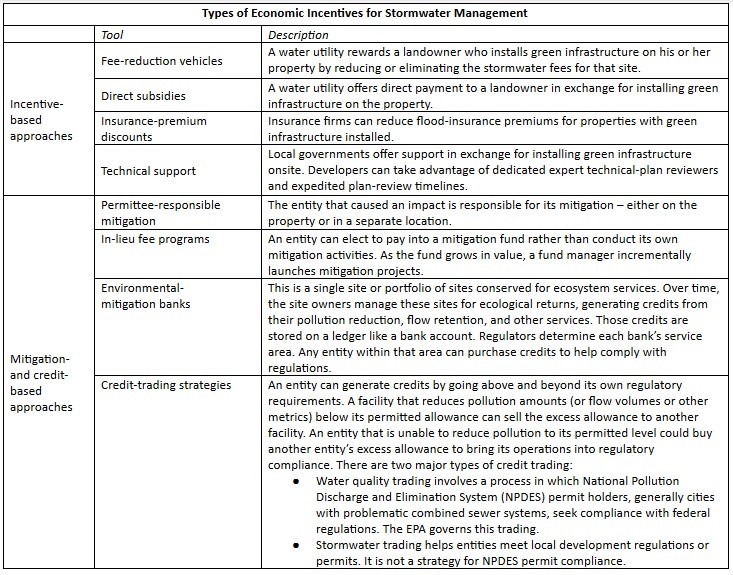

The report focuses on two major types of economic tools, incentives and mitigation/credits. These are outlined in the table below.

Incentive-based approaches encourage private citizens to help achieve stormwater management goals. The key strategies are cost avoidance, financial gain, and program support. Many rely on the stormwater fees that utilities charge for impervious land, water volume, and other factors. The water volume may relate to either the amount discharged or the amount consumed.

Mitigation- and credit-based tools give entities flexibility in meeting regulatory requirements. Individual businesses and public agencies face different costs in complying with stormwater-management mandates. Site locations, financial assets, and other factors drive the variation in expenses. These tools direct investment toward the most cost-effective tools and locations for providing stormwater benefits.

Overcoming Barriers to Implementation

As the report says, stormwater-management programs that use economic instruments are the exception, not the norm. Incentive-based and credit-based programs face significant challenges. Participation in incentive-based programs is often lower than expected, Sanneman said, while credit-based approaches can be prohibitively expensive and complicated to develop and implement.

In the report and a subsequent interview, Sanneman identified five critical steps for communities seeking to overcome these barriers. Communities can build fee bases, consider installation lifespans, use effective storytelling, create transferable templates, and find stakeholder champions.

Building a Fee Base

Dedicated, adequate funding streams are rare. The single most effective tool to enable implementation of green stormwater infrastructure, Sanneman said, would be granting municipal MS4 permittees the authority to charge stormwater utility fees.

Over 7,500 United States communities have regulated separate storm sewer system (MS4) permits. (Another 770 communities have regulated combined sewer systems.) The Green Infrastructure Leadership Exchange estimates that fewer than 1,500 of those MS4 programs — less than 20 percent — have developed user-based fee programs specifically for stormwater infrastructure.

Enabling utility fees “would drive innovation and enable adoption and implementation of proven tools in new communities,” Sanneman said. “Agencies need the ability to fund incentives, fund rebates, and find the resources to dedicate a staff person to figuring out green infrastructure. A dedicated funding stream would make a huge difference for many communities.”

According to the report, legal barriers may stand in the way. Stormwater utility-fee revenue is often constrained by legal obligations. Those rules may restrict spending to system operations, maintenance and rehabilitation while effectively prohibiting innovative green infrastructure. Stormwater managers must justify how those investments meet stormwater goals.

Stable funding would also enable agencies to set rebates and subsidies at appropriate levels. Rebates that do not cover the cost of a project cannot effectively motivate property owners to install green infrastructure. With stronger funding, agencies could also leverage subsidies by layering on additional incentives. For example, they could couple technical assistance with cash payments.

Finally, changing the federal tax code could speed adoption of onsite green stormwater infrastructure. The Internal Revenue Code treats subsidies as taxable income, which makes them less attractive to property owners. According to the report, this change would bring classification of green infrastructure subsidies into alignment with classification of clean energy subsidies.

Considering Credit and Installation Lifespans

Incentives must factor in maintenance obligations, addressing the long-term upkeep of infrastructure to keep it performing well. According to the report, maintenance agreements and lifecycle funding can help motivate property owners to maintain their green infrastructure installations.

Better data on long-term performance of installations will also help. With more information, agencies and property owners should feel more confident in predicting the effort and cost to maintain the functionality of installations over time.

Credit-market developers must also consider the permanency of their credits. On credit-trading markets, developers can offer long-term or short-term credits. Entities generating credits have more flexibility when those credits have short lifespans.

A permanent credit would limit development in perpetuity, but a several-year-long credit maintains a wider range of options for future uses of the site. According to the report, this strategy could encourage more participation in new markets and keep credit prices low.

But credit buyers, like land developers who seek regulatory compliance through their purchases, could be put off by the uncertainty.

“We need to make a product that buyers want,” Sanneman said. “Credit buyers like developers and transportation agencies don’t know about restoration, they just want to get their projects through permitting.”

One possible solution would be public-sector guarantees or supports for credits on repurposed sites.

“If credit trading is sophisticated,” Sanneman said, “I think governments are much more likely to be able to make backstop guarantees.”

Telling the Story Effectively

Innovative cities and stormwater utilities lead with strong communication.

“The leading thinkers tell their stories well,” Sanneman said. They sell their green infrastructure projects effectively to both the general public and to their boards. Convincing multiple audiences includes sharing both scientific data and human storylines.

This storytelling can make the difference when green infrastructure is weighed against traditional gray infrastructure. Federal regulations are the primary drivers for public and private stormwater-management investments.

However, when major infrastructure investments come before municipal leaders for budget approval, ancillary benefits associated with green options can tip the scale from gray to green infrastructure for regulatory compliance

For example, Sanneman said, utilities can sell green infrastructure based on benefits for climate resilience, local economic development, and enhanced ecosystem services.

Leading agencies also encourage internal skill-sharing and bridge-building. Holistic water management approaches can encourage projects with the highest overall returns for a community. For example, encouraging floodplain managers and stormwater managers to work together can lead to new solutions.

“They both deal with wet weather, but they rarely work together,” Sanneman said. So they miss out on integrated approaches can encourage multi-benefit projects. (A new Willamette Partnership report details nine ways that stormwater and floodplain professionals can work together.)

Creating Templates

Large stormwater agencies have often led the way. This is because they have in-house technical staff who can support green infrastructure implementation and understand financing nuances, Sanneman said.

Developing a trading or mitigation program is complicated and expensive, often prohibitively so, for small communities. Although community-specific variations limit the transferability of infrastructure plans, Sanneman believes that large cities can pave the way for smaller communities.

According to the report, guides, webinars and workshops can accelerate knowledge-sharing between communities. This would help overcome small agencies’ lack of specialist resources in infrastructure financing, policy/regulatory analysis, and legal support.

Templates may also help quantify credible units of trade. A proxy value could be easier to measure than specific pollutant levels. The report notes that basing trading currency on the right proxy could make trading less expensive to implement and measure.

Runoff retention or sediment levels could be helpful proxies for nitrogen and phosphorus levels, for example, because they are easier and cheaper to measure.

Any proxy measurement would require regulatory approval.

Finding Champions

Finally, communities that have successfully implemented green infrastructure usually have champions within public agencies.

“It’s empowering and disheartening at the same time,” Sanneman said. “It’s empowering to know that having an enthusiastic person can help projects succeed and can drive innovation. But if you don’t have that person, how do you create champions? How can external advocates focus their efforts on communities with the best chances of progress?”

Ideally the champion is in leadership at the public agency or utility, Sanneman said. That champion will need to convince the board of directors or supervising commission. They will also need to convince people up and down the chain of command within the agency — a classic lesson in change management that has proven widely applicable in this work.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or email the author via our contact form.