A Blueprint for Financing Green Stormwater Infrastructure

This is Part 1 of a two-article series.

In a few Rust Belt cities that are seeking economic and social benefits, Greenprint Partners – formerly known as Fresh Coast Capital – is breaking new ground by financing fresh solutions for green stormwater infrastructure. It is using a combination of municipal, private and government resources. Its goals are to create a replicable model and expand the market.

According to a case study from The Kresge Foundation, “While science supports the use of green stormwater infrastructure, many municipalities remain reluctant to adopt these practices due to a lack of capacity, expertise and/or capital.”

In an interview, Nicole Chavas, CEO and cofounder of Greenprint Partners, described the growth her company hopes to catalyze in this emerging market. It is currently working in Peoria, Youngstown, and St. Louis. It is considering a new project in Philadelphia.

CFN: I’d like to hear an overview of Greenprint Partners’ grant from The Kresge Foundation for green stormwater infrastructure development. What is its purpose, size, timeline and structure?

Chavas: There are two different types of capital.

It’s a $500,000 grant that’s coming from the environmental program. It’s an 18-month grant.

And then it’s also a $750,000 program-related investment. And that’s an investment directly into our management company through a convertible note structure from their social investments team.

The grant is specifically for program development for work we’re doing in St. Louis. And the investment in our company is for gross capital to help our business grow and enable us to continue to develop our product and scale product.

CFN: Let’s dig into the situation in St. Louis more. How do you think this project will impact communities on the ground there?

Chavas: There are plenty of significant opportunities for impact.

We hope the model that we develop in St. Louis can be replicated.

The context for this grant is that the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District, the sewer and water authority in St. Louis, has a green infrastructure program - a grant program where every year, it provides capital to private-property owners who are willing to install green infrastructure on their sites to help keep water out of the storm systems and keep pollution out of the waterways.

And what we found when we looked into it further was that this program had very little uptake, particularly from low-income communities. And when it [did], it was being taken advantage of by large commercial properties like IKEA.

Obviously, green infrastructure anywhere has a positive impact, but not quite the level of impact as [it would have] if you get that green infrastructure into the communities that need it the most.

This program wasn’t well-marketed, so a lot of people just didn’t know about it. Green infrastructure wasn’t something a lot of communities were aware of. Some people just didn’t know what it was or how it could benefit them.

And from there, just [to be] able to participate in the program, a property owner would need to hire an engineer to design the projects, do the grant funding… do the work, and then get reimbursed.

Particularly in low-income communities, that level of time, effort and capital is just not available for them.

That’s why we developed a business model where we could go out and actually aggregate. [We] go out and recruit property owners, particularly in the neighborhoods that fit our mission. We aggregate them, find an engineering partner, do all that design work, develop a project, submit the applications on their behalf, get approved, implement the project, get reimbursed, and then basically deliver… green infrastructure.

We do that by actually designing it in a way that is most meaningful for the community of that property owner.

Churches, for example, are a great target for these types of programs because there are hundreds of them, they have huge parking lots… and they’ve got a community that they can really engage around these exciting environmental opportunities.

So in St. Louis, we’re actually working with three different properties for this first round of the program. One’s a church, one’s a Catholic social services center, and one’s a vacant property that’s going to be the greening hub for that community.

For each of those projects, we worked with hosts to identify what’s most meaningful for them in getting green infrastructure implemented on their sites. We designed it to their specifications while also meeting the needs of the sewer authority in terms of actually designing it to keep water out of the sewer system, which is a goal of the water authority.

And our projects have been conditionally approved and are expected to be constructed this spring.

CFN: Are you planning to expand to other locations in St. Louis or do different projects there?

Chavas: This program in St. Louis is an annual process. Every October, they put out a call for submissions for applications. These projects came out of our application to their October 2018 call for projects.

And so every year going forward, we plan to do exactly what we just did with another round of landowner partners. So this coming October, we’ll be putting together a similar portfolio, submitting it for applications, getting approved, securing financing… that entire process.

And then we’re taking that model to other cities that have these types of grant programs.

Philadelphia’s another one that has this type of grant program. And we’re looking to put together a similar portfolio for application for their upcoming cycles as well.

Part of the goal of why Kresge provided funding for this is not just to create a program in St. Louis, but also to create a model that could be replicated elsewhere so that grant can have a sustainable impact above and beyond the initial project it’s helping to fund.

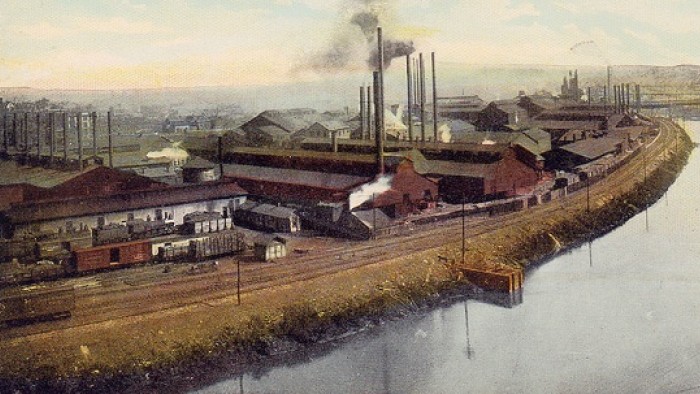

inhabited since the early 1700s. Greenprint Partners is

considering a potential project in Philadelphia.

Celine Herrand/Flickr

CFN: If you decide to expand the project, would The Kresge Foundation provide additional money? Or would you try to look for resources elsewhere?

Chavas: The goal with this grant is that with this one-time program-only grant, we would have the tools we need to be able to scale without additional grant funding.

We’re a for-profit company, a B-Corp. And we’re looking to create real market opportunities that can scale green infrastructure.

Given the very early stages that green infrastructure funding is in, philanthropic funding is very essential to move this space forward… to have real sustainable markets that can enable green infrastructure to scale without that philanthropic funding.

In moving to Philadelphia, we do not necessarily need another grant, but [we need] to maybe move to the next level of how philanthropy can play a role in moving it forward and reduce program-related investments.

How can philanthropy use low-interest loans and other financial structures to move this beyond just pure grant capital? That’s something we are always thinking about too when working with our philanthropic partners – how can you be creative with the use of their capital to help the market?

CFN: I’m interested in hearing an overview of the work you’re doing in Peoria with your grant from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Conservation Innovation Grant (CIG) program. What is this grant’s size, purpose, timeline and structure?

Chavas: Peoria’s really exciting. It’s a little over 100,000 people – a small Midwestern city. It is seeking to become the first city in the country to meet its compliance requirements for stormwater with 100-percent-green infrastructure.

While it’s waiting to finalize that, it’s looking to get pilot projects placed. It wants to continue to engage the community around the green infrastructure.

We partnered with Peoria to secure this grant from the USDA CIG program and won a $1-million grant with a $1-million match to pilot what we’re calling a stormwater farm. Project partners provided the matching funds.

We partnered with Peoria to take a vacant city-owned property and turn it into a model for green infrastructure and also participate with the local community in doing urban agriculture.

That site… is now an actively managed urban farm that also has a series of green infrastructure installations that are now actively managing stormwater from the neighborhood in a low-income community.

We’re hoping that can also be a model. Peoria can also think innovatively about the land, about the challenges it’s facing, and find ways to move the needle on things.

In this neighborhood in Peoria where this vacant property exists, there was a food desert. [People] were looking for new ways to bring urban agriculture into the neighborhood.

And simultaneously, the city was looking to demonstrate some of this exciting green infrastructure practices.

So we applied for that grant and were awarded that in 2016. We just had a ribbon-cutting June 30.

It’s been a year and a half of work to design, engage the community in what their interests were, use that to inform the design, and, in the spring, actually construct the urban agriculture parts of it – as well as the bioswales and the stormwater forest.

Note: Some minor edits from Greenprint Partners were added to this article on 9/4/2018 and 9/5/2018 - including changes to two dollar amounts.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.