Louisiana Environmental Impact Bond May Reduce Coastal Land Loss

Bordered by beautiful wetlands along the Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana is a hub of transportation and industry. A pilot environmental impact bond could seed a set of wetland-restoration projects for the state. Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Quantified Ventures, and their project partners are proposing to draw on funding from the Deepwater Horizon oil-spill settlement to make this happen.

The proposed pilot-project location is Port Fourchon, which is on the Gulf Coast. This port is a crucial node for shipping and energy. But land loss due to coastal erosion and storms threatens to shut it down.

“If you look at a map of Port Fourchon, you’ll see there is one access highway that is very exposed,” said Carolyn duPont, director at Quantified Ventures. “And then the port itself - all the infrastructure, including all the docks and all the buildings that are on the site - is pretty low-lying and very vulnerable to storms.”

According to a report the team has produced, Louisiana loses over 1.3 acres of land every 100 minutes as wetlands become open water. Over the next half-century, the state will lose an area close to the size of Connecticut due to coastal erosion, sea rise, and marsh damage if no action is taken.

This has a brutal effect on the state’s economy and safety. Storms and erosion are wiping out coastal communities.

But environmental restoration could help stem the tide of land loss.

The state of Louisiana recognizes this emergency. It has created a Coastal Master Plan directing $50 billion of investment from multiple sources over 50 years toward structural and shoreline protection, hydrologic projects, marsh creation, island and ridge restoration, oyster reefs, and sediment diversions.

This would reduce land loss by 513,920 acres. It would also save the state $150 billion in storm-damage costs. If carried out, the plan would create a resilient Mississippi River Delta where communities, commerce, industries and fisheries could still thrive. The Coastal Master Plan has a very solid base of support, the report said – including unanimous state legislative backing.

This pilot project would fulfill a part of this plan.

“The reason that we think a corporation or an asset owner might be interested in participating in this transaction is basically the ability to stay in business in that geography,” duPont said.

“We were impressed by how positive the responses were,” duPont said after hearing from a large number of stakeholders.

Potential partners who might provide performance payment are expressing interest in the project, said Shannon Cunniff, director of coastal resilience at EDF.

“In our engagement with [United States impact] investors, there was a lot of interest in supporting Louisiana,” duPont said. “There are a lot of opportunities to engage investors around the country in Louisiana’s efforts and support those efforts.”

What Role Energy and Industry Play

In addition to the massive state-level economic advantages described above, protecting Louisiana’s coastal industries is crucial from a national energy-security standpoint.

“Probably 20 percent of the nation’s energy comes through here,” said Steve Cochran, associate vice president of coastal resilience at EDF. “We’re trying to create a line of defense within a multiple-line-of-defense strategy.”

ConocoPhillips, a fossil fuel company, owns the wetland where the pilot restoration project might be sited. Initial conversations have shown the company is interested in hearing more about the potential project, duPont said.

How the Financing Model Would Operate

“The feedback from investors was to keep things simple, especially for the pilot,” Cunniff said.

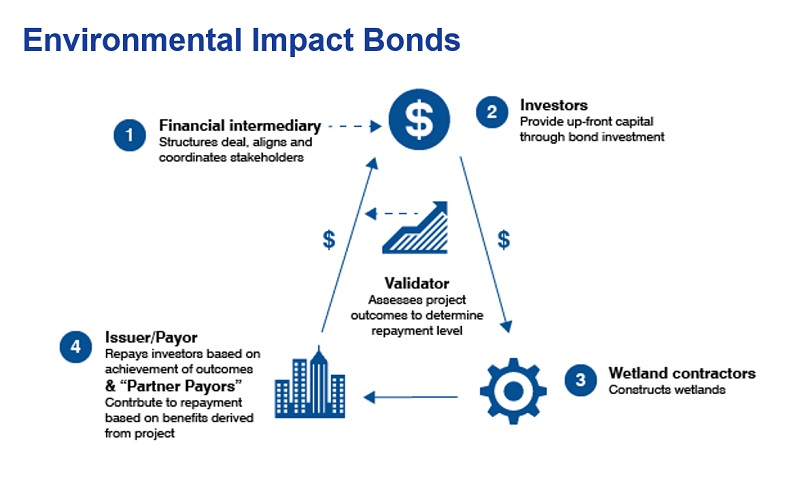

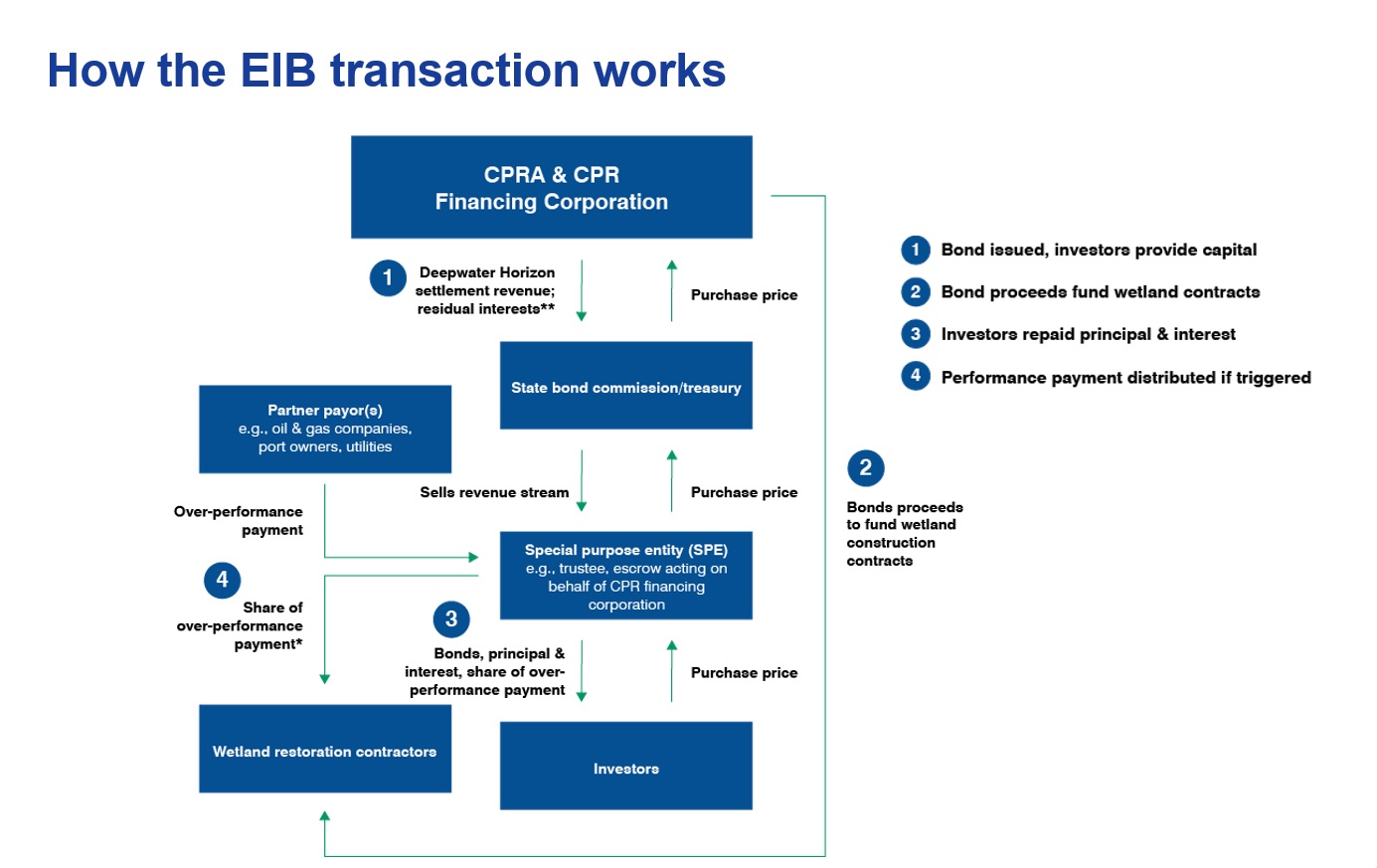

The report proposes a straightforward two-tier environmental impact bond transaction with a $40-million investment, as shown in the diagram above.

The model would involve creating a relatively simple bond with a performance payment for wetland improvements. The $40-million bond would be issued by the Coastal Protection and Restoration Financing Corporation (CPRFC). Impact investors would buy into it.

Most environmental impact bonds work similarly to traditional bonds. They have a fixed interest rate and a set term. There is an additional bonus performance payment made to investors if the projects perform above a specific threshold.

When Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) looks at the sources of revenue that could be used to repay the bond, it sees multiple options. It has already identified $9.16-11.76 billion in funds for the $50-billion Coastal Management Plan. Funds for wetland restoration would mainly come from the Deepwater Horizon settlement combined with revenue from oil and gas production leases from federal waters.

“The repayment of the bond to investors depends on the extent to which the environmental results are achieved,” Cunniff said.

The success of the bond depends on the performance of the marsh-restoration project. Avoided land loss will indicate that the restoration has succeeded.

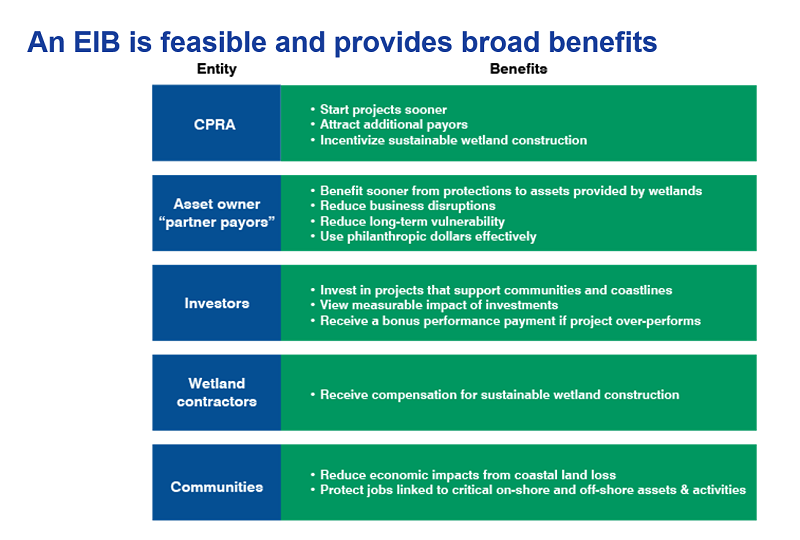

The table below shows the benefits stakeholders can expect.

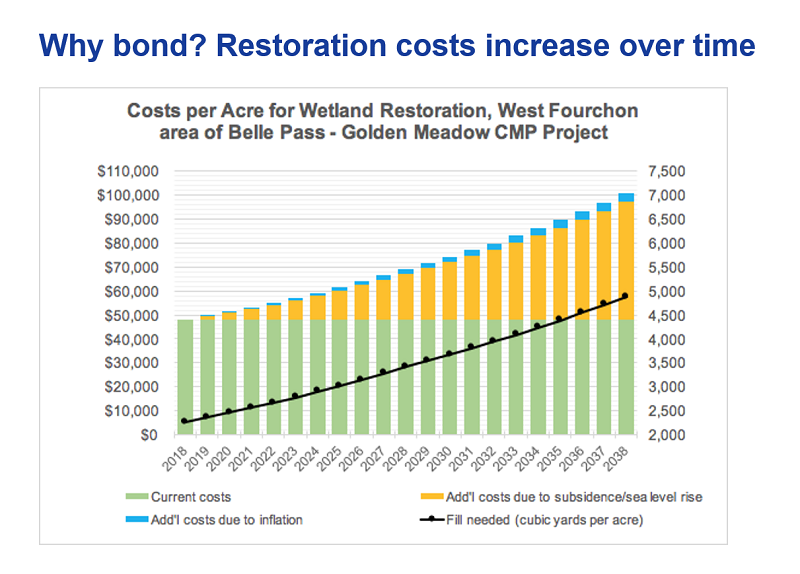

Time creates a crucial financial hazard for this project. As sea-level rise occurs and marshes sink, it becomes more and more expensive to restore shoreline marshes. The graph below shows how costs increase over time.

Constructing projects today rather than waiting a decade could save CPRA around $17.6 million for a $40-million project of this nature.

Why Developers Face Risks

In any wetland-restoration investment on a storm-facing coast, natural and financial risks can occur.

Natural physical risks can include unreliable sediment retention or weak vegetation growth.

Storms can create risks of wetland damage. CPRA typically bears this risk financially for its work and attempts to salvage projects by using contingency funds or reducing project size.

Contractors may not succeed when reconstructing wetlands if they have difficulty obtaining permits or sediment. Equipment maintenance, construction complications, or financial problems can also hold back construction.

Using Deepwater Horizon settlement funds may increase the perceived risk because the CPRA cannot use the state’s credit rating.

Investors said they would like to know the specifics of how CPRFC can access Deepwater Horizon funding – and what restrictions and options exist. This is an issue that CPRA and CPRFC would resolve by consulting legal advisors who are familiar with state laws.

A credit-rating agency will assess the prospective bond. CPRFC has never issued a bond before. Investors will then evaluate whether CPRA is creditworthy.

How the Idea Began

“This idea has its genesis in need,” Cunniff said. It began with an expert survey and workshop that focused on coastal restoration in Louisiana. This led to the decision to start a pilot marsh-restoration program at Port Fourchon.

“To select the location around which a conceptual environmental impact bond could be created, we evaluated 31 Coastal Master Plan projects. We looked across the coast -and looked at storm exposure and the economic assets that are at risk,” Cunniff said.

The team used data from the United States Army Corps of Engineers and Rand Corporation.

“In the end, we settled on the Belle Pass-Golden Meadow project area,” Cunniff said. “We selected that particular site due to its proximity to and its key role in facilitating offshore oil and gas production.”

“With the site that we’ve chosen, it’s primarily economic and employment protection that they’ll receive,” duPont said.

What the Next Steps Are

According to duPont, the team is “lining up a meeting with CPRFC that will happen toward the end of the year.”

What will the timeline be for the bond’s potential approval and availability?

“That is definitely the million-dollar question,” duPont said. “We’re estimating that the approval process with CPRA would be somewhere around six months - optimistically. That timeline is in their control and has to do with their board’s scheduled meeting. If and when they say ‘Yes, we are ready to pursue this’… it would take somewhere around nine months to pull the transaction together and get it issued. So the question is: ‘When does the approval happen?’”

Structuring the transaction is likely to take six to eight months. As this moves forward, CPRA and CPRFC may choose to use a different or larger site. They will sign agreements with a project partner and collaborate to structure the transaction. They will also work with a financial intermediary.

Other communities throughout the nation may use this concept as a springboard to develop similar projects. The discussion is piquing their curiosity.

“We’ve had conversations with other communities on coastlines across the United States that are thinking about wetland restoration as a natural infrastructure tool,” duPont said. “Most communities across the coasts… are evaluating wetlands. It’s new to think about it in terms of valuing performance. A lot of ports have to deal with… sea level rise.”

Note: Nathalie Woolworth contributed reporting and research to this article.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.