Tapping into Public Health Dollars to Restore Urban Forests

Recent developments on the relationship between urban greenery and public health have taken cities by storm. Reports such as “Funding Trees for Health" by The Nature Conservancy and the “Green Infrastructure and Health Guide" by the Willamette Partnership and Oregon Public Health Institute have made the case clear.

Nature in urban areas has the potential to be a form of public health infrastructure. Crystallizing and communicating this connection signifies a turning point. Experts in the urban forestry and public health fields are now exploring mechanisms to implement community health projects by funding urban greening.

As the benefits of trees for public health become established, urban forestry and public health entities can not only align toward a shared goal but also can develop a financial relationship that is mutually beneficial and reinforcing.

Bridging Urban Forestry and Health Finance Streams

“Funding Trees for Health” stresses the importance of closing the finance loop linking urban forestry and public health.

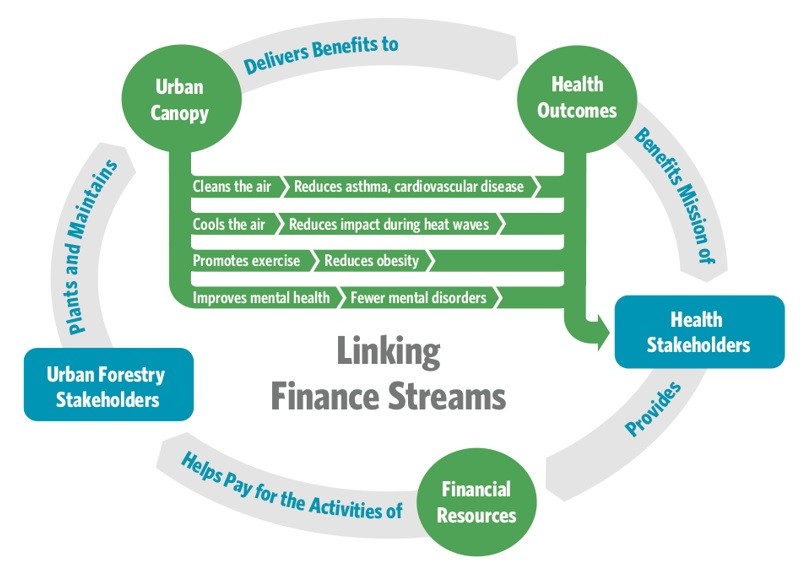

Currently, urban forestry programs that plant and maintain trees and other urban greenery deliver benefits for public health. This reduces costs for the health sector and supports its mission of improving wellbeing.

To close the loop, public and private health institutions would benefit from investing financial resources in the urban forestry programs that yield health benefits. The first image below illustrates this concept.

Linking these finance streams is important for closing the urban forestry investment gap.

According to “Funding Trees for Health,” the urban forestry investment gap in the United States is “the need for additional money for adequate maintenance of existing canopy ($1.87 per person per year), plus additional investment to expand urban forest canopy to seize the kind of potential health benefits outlined in the “Planting Healthy Air” report ($5.87 per person per year).”

The report says that a “modest 0.10-percent increase in overall health spending amounts to an extra $10 per person per year,” which “would close the investment gap in urban forestry.”

To quantify the value of trees to the public health sector, The Nature Conservancy used a Co-Benefits Risk Assessment (COBRA) model. The model explores scenarios in which trees are planted in the sites with the greatest expected health benefits from particulate-matter-concentration reductions.

However, it still found that — at the very least — avoided health-related costs offset tree planting and maintenance costs by as much as 30 percent in Miami, 23 percent in New York City, and 19 percent in Los Angeles.

If the health sector were to consider other pathways for health benefits, such as those related to recreational opportunities, water quality, public nutrition, or social cohesion, these offsets could be much greater.

Mechanisms for Closing the Finance Loop

Dr. Robert McDonald, the lead author of “Funding Trees for Health” and lead scientist for the Global Cities program at The Nature Conservancy, said there are two steps to connecting urban forestry and public health. The first is to engage public health agencies or institutions in the planning around urban forestry. The second is to link the finance streams.

One potential funding stream that would help close this loop is from health sector philanthropy. “Funding Trees for Health” found that a mere 0.8 percent of the annual United States health sector philanthropic donations would be enough to pay for the costs offset by improved health from reduced air pollution if the nation was to close the urban forestry investment gap.

“Funding Trees for Health” introduces other innovative finance mechanisms. For instance, while no current case studies exist, the report suggests that major insurance companies could accept community-level rates for policyholders located in cities improving their urban green spaces.

To incentivize cities to participate in the greening program, health insurers benefiting from greener communities should return a portion of the economic benefits to participating communities. For example, these monetary returns can finance further tree plantings and maintenance, which would partially offset the additional greening costs.

Within the public sector, “Funding Trees for Health” highlights the Accountable Communities for Health (ACH) Innovation Model under the Affordable Care Act as another appropriate source of funding. ACH focuses on health interventions that “address the community-level factors shaping population health, including social, economic and environmental determinants.”

This community-health focus makes the ACH program a natural fit for funding projects that intersect public health and urban forestry.

At the local level, “Funding Trees for Health” recommends a simple pathway: ensure health agency budgets contain a line item for urban greening. While municipal public health departments are typically small, a small contribution to urban greening can be significant. In particular, the health agency can collaborate to build health co-benefits into the city’s urban forestry priorities.

McDonald said some health policy foundations are starting to get interested in the topic. For example, he said, “Kaiser Permanente has made big investments in parks and nature.” These are mostly related to enhancing recreational opportunities for health outcomes.

However, “the big money is in public sector institutions or insurers, but those kinds of institutions are somewhat hesitating to invest in nature for health,” McDonald said.

Reframing the Value of Urban Forests

Introducing these new streams of funding and fortifying the connection between health and nature is critical for reversing current trends in urban forest degradation.

In many cities across the United States, trees have historically been treated as a luxury good. When municipal revenues stretch thin and budgets need skimming, urban forestry programs have been considered expendable relative to other critical public services.

Urban tree stocks continue to decline at a rate of about 1.3-percent, or 4 million trees, each year. Urban forestry programs have seen a 25-percent decrease in funding relative to their spending capacity in 1980.

Barton Robison, co-leader for the Health & Outdoors Initiative with Willamette Partnership and collaborator for the “Green Infrastructure and Health Guide,” stressed that improving urban ecosystems for public health is even more important “as we think of climate change and the health challenges and risks that it poses, especially for vulnerable populations.”

“Hospitals can be working now to address these long-term issues in a preventative way to make a difference for some of these vulnerable communities,” Robison said. “Hospitals have a unique opportunity to change the way that nature is used in a community. Not only can hospitals be places people go when they’re sick, but also [they can be] stewards of community health.”

McDonald also said public health funding “can absolutely be a driver to address urban tree canopy inequities.” MillionTreesNYC is one example. It made an explicit effort to focus on neighborhoods that had disproportionately low tree canopy cover and high pediatric asthma-hospitalization rates.

Strengthening the Urban Forestry and Health Finance Connection

Despite the important role that nature plays in supporting community health, Robison said that more work lies ahead to clearly outline the connection.

“It’s really clear that nature therapy has profound effects on preventing disease. The gaps in the research are what exactly those dosages are and [what] the mechanisms of causality [are]. How much nature do you need to see those benefits? What are the things your body is responding to outdoors?” Robison said.

McDonald stated that the University of Louisville School of Medicine approached The Nature Conservancy to conduct a study, with support from the National Institute of Health, to answer these types of questions. The study, called the Green Heart Project, is the first controlled experiment to examine urban greening with the same rigor as a new pharmaceutical intervention.

This study will be critical to further quantifying the economic benefits of trees for health and will bolster the ability to build financial streams between the two fields.

Funding Urban Forestry for Health Can Address Specific Community Challenges

Public health impacts and stressors vary from neighborhood to neighborhood and from health sector to health sector, so engaging diverse expertise and community input will inform the development of solutions.

“In Portland, some neighborhoods with little canopy cover are experiencing high rates of asthma. There, it makes sense to invest in canopy cover,” Robison said.

However, other cities or institutions may be interested in walkable cities and recreation, McDonald said. Neighborhoods, agencies and institutions will have “different overlapping but distinct agendas in health and nature.”

Robison stressed that the areas where urban forests and green infrastructure will have the “most profound health effects” are in communities that are “most affected by inequities.”

“A lot of the people who are suffering system-wide inequities aren’t able to get outside to the mountains for the week or leave the city and go to what a lot of us think of as the natural world,” Robison said. “If we can get community health providers to invest in green infrastructure, it can have profound effects on the whole community and address system-wide inequities.”

Note: The Nature Conservancy has donated to Conservation Finance Network.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.