Wells Fargo Funds Minority-Owned Green Businesses in North Carolina

After decades of underinvestment, African-American farmers and small business owners in North Carolina will now receive green enterprise loans from Natural Capital Investment Fund (NCIF). The award of $1.6 million, announced on May 3, is part of a much larger program by Wells Fargo that seeks to fill part of the huge void in bank financing of minority-owned businesses.

This financing will support energy efficiency, solar power, sustainable agriculture, and a healthy local food movement. It will build on NCIF’s existing expertise in funding similar projects locally.

When Wells Fargo opened a window of opportunity through its $75-million Wells Fargo Works for Small Business®: Diverse Community Capital program for the first round of funding in 2015, it was snowed under with interest. Out of the 100 applications, the bank has funded 15 so far.

This shows there is a massive unmet need here that other banks can step forward to fill.

Reaching an Underserved Market

Historically, African-American farmers in North Carolina have often been driven out of business due to uncertainties in agriculture such as changing yield volume, fluctuating crop prices, and varying government policies. A federal class action lawsuit attempted to address structural inequalities, but many farms still closed their doors. Today, financing similar farms and agriculture-related businesses remains challenging.

Marketing loans to rural small business owners, especially farmers, requires building a groundwork of trust and communication.

“Farmers talk to farmers. They trust farmers probably more than they trust anyone else,” said Rick Larson, senior vice president and director of strategic initiatives at NCIF.

Larson said that within the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) administration “there are states that are really trying to make an effort to increase the percentage of their staff that are minorities and are sensitive to working with minority farmers.”

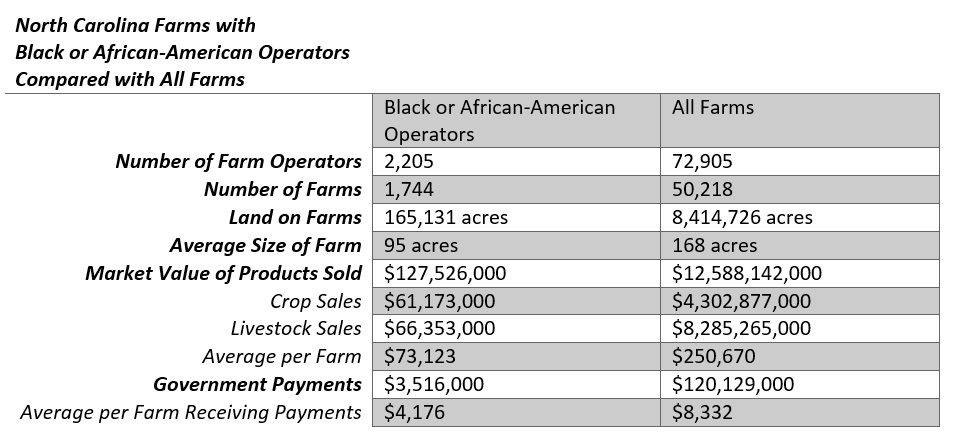

According to data NCIF collected from the USDA, African-American-owned farms in North Carolina are around half the size of average farms. They generate under 1/3 of the average income of farms in the state. The farmers are also around four years older than the overall average.

“African-American farmers have been declining over the last number of decades,” Larson said. “Part of our mission is to help those farmers stay on the land.”

NCIF operates in nine states in Appalachia and the Southeast. Founded as a support organization for The Conservation Fund, the community development financial institution (CDFI) supports green businesses throughout this region.

“We don’t just focus on African American farmers and borrowers,” Larson said. “We’ve lent to all ethnicities, including Caucasians. North Carolina has one of the fastest-growing Latino populations in the country. There may be benefits to a Latino city resident knowing that strawberries came from a Latino farmer in North Carolina.”

Larson said NCIF is planning to ramp up its face-to-face marketing activities to build conversation about these loan opportunities. These will include visits to conferences, participation in listservs, and individual outreach to farmers. NCIF plans to hire a lender to be “on the ground” in the community.

“On our board, we have a high-level person at the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services whose docket is to work with the minority and low-resource farmers,” Larson said.

Transforming the Local Food Movement

At this time, Larson said, “I would say the minority community, both on farms and in urban areas, is not able to participate very successfully in the local food movement.”

Providing loans can help to bring minority business owners into the local food movement in both urban and rural areas.

NCIF is taking a supply-chain approach to financing that supports businesses at all levels of this ecosystem. From funding greenhouse tunnels made of polyethylene to encouraging produce distribution in urban communities, NCIF plans to support a growing chain of green businesses.

“You have to have the markets to create the pull,” Larson said. “Farmers have to know there is a market if they’re going to grow bok choy or radishes. The opportunity we’ve got is to continue to build the local food supply. That’s the challenge.”

Bringing social equity into the local food system can help business owners build wealth, send their children to school, buy homes, and create jobs.

“That’s the vision,” Larson said. “This is a big economic development tool for small towns across our region. The loans have lots of ripple effects that are really important for rural communities. A lot of towns had a small textile mill or furniture factory. Those times are long gone.”

Designing the Financing Options

According to Connie Smith, senior vice president and program manager for the Wells Fargo program, the NCIF funding consists of both grants and debt. A $600,000 grant has been combined with a $1 million equity-equivalent investment at a low interest rate of only 2 percent.

“We’re not a regulated institution, so we’re able to be flexible with our terms,” Larson said. “We will sometimes structure a loan so that it is interest-only. It can be amortized over a longer period. Our hope is that those borrowers will be able to refinance with a traditional bank or lending institution.”

Wells Fargo created its three-year-long program in response to the results of a Gallup survey that it commissioned. The responses, released in May 2015, revealed that African American and Latino business owners were often in search of capital for startups. The program is not specific to green businesses.

“They’re interested in accessing capital but have had challenges,” Smith said. “The primary goal of this program was to increase lending.”

CDFIs that Wells Fargo selects go through a rigorous evaluation and grading process. Wells Fargo staff look to see how their marketing and outreach works, view portfolio performance data, and require annual performance reports.

“We’re going to be asking for a lot of information,” Smith said. The January annual reports will include lending volume data, dollar values of loans that were made, numbers of businesses financed, total numbers of jobs created, numbers of minority-owned businesses financed – and, if possible, data on credit-score improvements.

Building Larger Outcomes

Wells Fargo is attempting to leverage the results of this program to transform the landscape of lending to minority communities. To accomplish this goal, Smith said, Wells Fargo is synthesizing best practices for underwriting, marketing and outreach.

The program considers three forms of capital: social capital, debts and grants.

Social capital includes developing capacity for future financing. In their evaluations, CDFIs will tell Wells Fargo what developmental services they have provided. Bookkeeping, business planning, and marketing can be included in these financing programs.

NCIF already offers an accounting service for farmers who do not have a CPA already. This program, “Accounting Assistance for Disadvantaged Farmers,” provides discounts on financial management assistance and bookkeeping. Larson said he expects this existing project will generate some referrals for the new loan program.

Wells Fargo is also analyzing other obstacles while it collects best practices.

“A line of credit for working capital has been identified as a real need,” Smith said. “Not every CDFI has the capacity to offer this product. Some do. Some have been very creative in offering this line of credit. If we can figure out how to make a line of credit accessible to more CDFIs, that could be a great outcome of this program.”

Because there is so much latent demand for these resources, Wells Fargo is considering how to expand the impact of its work in this arena and create broader system change in the banking industry. The bank is bringing together leaders and collecting their combined knowledge and learning.

“We had an extraordinary response,” Smith said. “While I wish we could provide funds to all the organizations that have approached us, were not able to.”

Reducing Energy Costs

Saving energy can help to cut costs for business owners in the local food economy.

“It’s really critical for our work,” Larson said.

Earlier, NCIF developed its Energy Efficient Enterprises (E3) Initiative. This initiative offers energy audits and consultations together with loans. Business pay little to nothing for the technical assistance due to grants from the USDA and other funders. Private capital also supports this initiative.

So far, 90 businesses have participated. Their average annual energy savings has been $11,380.

Larson said NCIF’s energy efficiency financing for food-system businesses has assisted breweries, bakeries, grocery stores, and farms.

“Breweries are a big user of electricity for their various processes,” Larson said. “We’ve got breweries that have done big solar installations. If they’re upgrading equipment, sometimes pumps and motors that are more energy-efficient can be helpful in reducing energy costs.”

One organic bakery was using a lot of hot water for cleaning its equipment, Larson said. “They installed a solar-hot-water system.”

NCIF’s clean energy financing covers energy efficiency, solar hot water, and photovoltaics.

The IGA grocery store chain is a customer of NCIF’s. “We’ve made loans to about half a dozen of those to help them replace their HVAC systems and lighting systems,” Larson said. “Lighting is certainly a big use in many businesses. Sometimes it can be something as simple as weatherization or insulation – conserving that cold air or that warm air.”

Farms use solar photovoltaics for electric fencing, pumps, and irrigation systems, Larson said.

Structuring Loans for Small Farms

Farmers face specific financial issues that non-seasonal business owners do not encounter. NCIF is proactively thinking about how to help farmers plan for effective repayment.

“We’ve been able to tie the repayment schedule to harvest time,” Larson said. “We did a whole set of loans to limited-resource farmers for grain bins. They get a better price for a grain than they might. The main element is just timing.”

This program, the On-Farm Grain Bin Project, lasted from 2008 to 2011. It was created in partnership with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. A report from NCIF shows that most farmers paid their loans off early. This success occurred because, after the bins were installed, the farmers were able to hold their grain until market prices were advantageous.

Larson said most of NCIF’s loans are at 5-7 percent, but some agricultural loans are at lower interest rates.

“Our loans are priced above where you would see a conventional agricultural loan be priced,” Larson said. “We’re not a below-market lender because we’re taking more risk than a traditional lender would.”

Small farmers are at a disadvantage when seeking financing, Larson said. This is because large agribusinesses can buy good crop insurance, but products from smaller farms are harder to insure. This makes owning a small farm financially rocky.

The USDA’s loan programs operate in parallel to NCIF’s. “We don’t want to compete with USDA farm service agency loans,” Larson said. “They’ve got the backing of the United States government to be able to do that. Our markets are borrowers and farmers who can’t, for whatever reason, access the FHA loans.”

NCIF and USDA are also collaborating through a separate program. This initiative, called Environmental Quality Incentives Program, helps farmers create wells and set up irrigation systems.

“We’re able to provide those loans at a low interest rate, 3-4 percent, that’s a great benefit for the low-resource farmers,” Larson said.

Note: The Conservation Fund, which is connected with NCIF, is a partner of Conservation Finance Network’s. The USDA has previously donated to Conservation Finance Network. Donors and partners outside CBEY and CFN do not review our articles or editorial calendar, but interviewees can review their quotes and Q&As.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group. You may also email the authors of any of the Conservation Finance Network's articles via our contact form or contact us via Twitter.